Journey to Liberalism

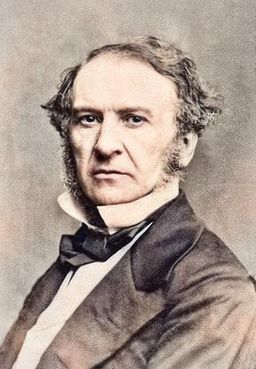

"Never forget that the purpose for which we live is our improvement , so that we may go out of this world having, in a great sphere or a small one, done some little good for our fellow creatures and laboured a little to diminish the sin and sorrow that are in the world." W.E Gladstone

Gladstone first entered the House of Commons in 1832, beginning his political career as a High Tory, which became the Conservative Party under Robert Peel in 1834. Gladstone served as a minister in both of Peel's governments, and in 1846 joined the breakaway Peelite faction, which eventually merged into the new Liberal Party in 1859.

Gladstone's own political doctrine—which emphasised equality of opportunity and opposition to trade protectionism—came to be known as Gladstonian liberalism.

Gladstone was re-elected as an MP in 1841. He was responsible for the Railways Act 1844—regarded by historians as the birth of the regulatory state, of network industry regulation, of rate of return regulation, and telegraph regulation. Railways were the largest investment (as a percentage of GNP) in human history and this Bill the most heavily lobbied in Parliamentary history. Gladstone succeeded in guiding the Act through Parliament.

Gladstone became concerned with the situation of "coal whippers". These were the men who worked on London docks, "whipping" in baskets from ships to barges or wharves all incoming coal from the sea.

They were called up and relieved through public houses, therefore a man could not get this job unless he possessed the favourable opinion of the publican, who looked most favourably upon those who drank. Publicans issued employment solely on the capacity of the man to pay, and men often left the pub to work drunk. They spent their savings on drink to secure the favourable opinion of publicans and therefore further employment.

Gladstone passed the Coal Vendors Act 1843 to set up a central office for employment. When this Act expired in 1856 a Select Committee was appointed by the Lords in 1857 to look into the question. Gladstone gave evidence to the Committee: "I approached the subject in the first instance as I think everyone in Parliament of necessity did, with the strongest possible prejudice against the proposal [to interfere]; but the facts stated were of so extraordinary and deplorable a character, that it was impossible to withhold attention from them."

Looking back in 1883, Gladstone wrote that "In principle, perhaps my Coal-whippers Act of 1843 was the most Socialistic measure of the last half century".

He resigned in 1845 over the Maynooth Grant issue, a matter of conscience for him. To improve relations with the Catholic Church, Peel's government proposed increasing the annual grant paid to Maynooth Seminary for training Catholic priests in Ireland. Gladstone, who had previously argued in a book that a Protestant country should not pay money to other churches, nevertheless supported the increase in the Maynooth grant and voted for it in Commons, but resigned rather than face charges that he had compromised his principles to remain in office.

Gladstone returned to Peel's government as Colonial Secretary in December 1845. "As such, he had to stand for re-election, but the strong protectionism of the Duke of Newcastle, his patron in Newark, meant that he could not stand there and no other seat was available. Throughout the corn law crisis of 1846, therefore, Gladstone was in the unique position of being a secretary of state without a seat in either house and thus unanswerable to parliament."

In 1846 Peel's government fell over the repeal of the Corn Laws and Gladstone followed his leader into a course of separation from mainstream Conservatives. After Peel's death in 1850, Gladstone emerged as the leader of the Peelites in the House of Commons. He was re-elected as MP for the University of Oxford at the General Election in 1847. Gladstone became a constant critic of Lord Palmerston.

In 1848 he founded the Church Penitentiary Association for the Reclamation of Fallen Women. In May 1849 he began his most active "rescue work" and met prostitutes at night on the street, in his house or in their houses, writing their names in a private notebook. He spent much time arranging employment for ex-prostitutes. In a "Declaration" signed on 7 December 1896 and only to be opened after his death, Gladstone wrote, "I desire to record my solemn declaration and assurance, as in the sight of God and before His Judgement Seat, that at no period of my life have I been guilty of the act which is known as that of infidelity to the marriage bed."

In 1850 Gladstone visited Naples. Italy, for the benefit of his daughter Mary's eyesight. Giacomo Lacaita, legal adviser to the British embassy, was at the time imprisoned by the Neapolitan government, as were other political dissidents. Gladstone became concerned at the political situation in Naples and the arrest and imprisonment of Neapolitan liberals.

In February 1851 Gladstone visited the prisons where thousands of them were held and was extremely outraged. In April and July he published two Letters to the Earl of Aberdeen against the Neapolitan government and responded to his critics in An Examination of the Official Reply of the Neapolitan Government in 1852. Gladstone's first letter described what he saw in Naples as "the negation of God erected into a system of government".

In 1852, following the appointment of Lord Aberdeen as Prime Minister, head of a coalition of Whigs and Peelites, Gladstone became Chancellor of the Exchequer. His first budget in 1853 almost completed the work begun by Peel eleven years before in simplifying Britain's tariff of duties and customs. 123 duties were abolished and 133 duties were reduced.

The income tax had legally expired but Gladstone proposed to extend it for seven years to fund tariff reductions. Gladstone wanted to maintain a balance between direct and indirect taxation and to abolish income tax. He therefore increased the number of people eligible to pay it by lowering the threshold from £150 to £100. The more people that paid income tax, Gladstone believed, the more the public would pressure the government into abolishing it.

The budget speech (delivered on 18 April), nearly five hours long, was written about by H.C.G. Matthew who said that Gladstone "made finance and figures exciting, and succeeded in constructing budget speeches epic in form... where careful exposition of figures and argument was brought to a climax" During wartime, he insisted on raising taxes and not borrowing funds to pay for the war. The goal was to turn wealthy Britons against expensive wars. Britain entered the Crimean War in February 1854, and Gladstone introduced his budget on 6 March. Gladstone refused to borrow the money needed to rectify this deficit and instead increased income tax by half. Spirits, malt, and sugar were taxed to raise the rest of the money needed. He served until 1855, a few weeks into Lord Palmerston's first premiership, Gladstone resigned along with the rest of the Peelites.

Conservative Leader Lord Derby became Prime Minister in 1858, but Gladstone—who like the other Peelites was still nominally a Conservative—declined a position in his government, opting not to sacrifice his free trade principles.

In 1859, Lord Palmerston formed a new mixed government with Radicals included, and Gladstone again joined the government (with most of the other remaining Peelites) as Chancellor of the Exchequer, to become part of the new Liberal Party.

This website is committed to the works and memory of William Gladstone. It is an independent project. © Copyright. All rights reserved.